Get to know Miguel Delibes

Fundación Miguel Delibes

DELIBES

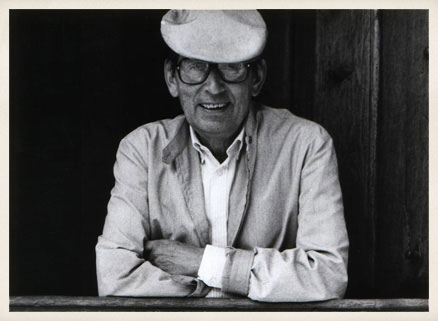

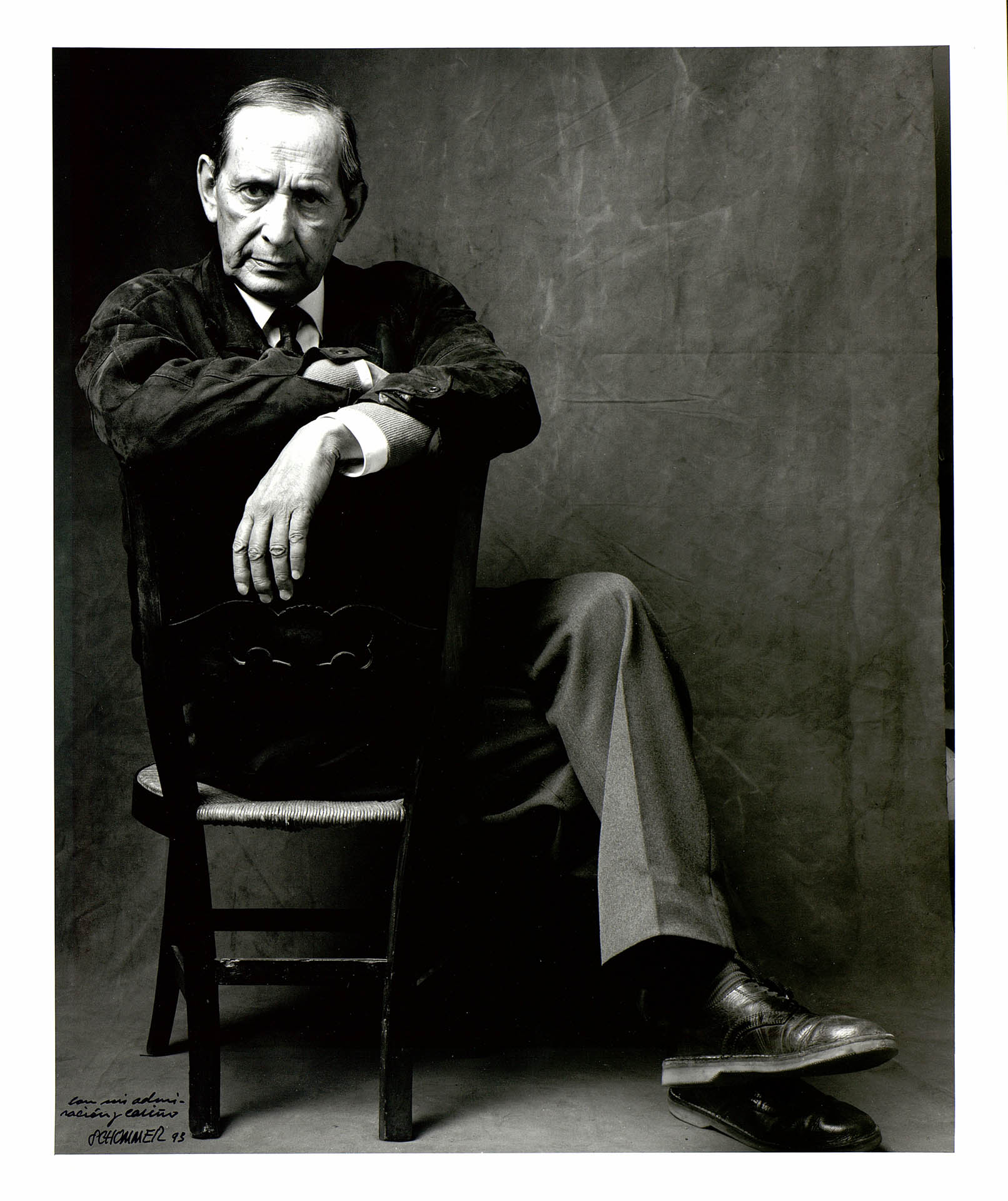

The man

He is a weird mixture between Professor and peasant, half refined, half natural whose calm voice can explode in a laughter, great communicator and a sad man dressed with a jacket, corduroy trousers and boots, not keen on watching TV or having debates, nowadays he would be something like a guerrilla member a resistance. He is, no doubt, a fellow from other time.

[…] He is, in a way, an outsider, a sniper who has one foot in his class while he kicks it with the other. Some would have loved that he kicked that class with both feet. Linked to the Upper-middle class of Valladolid because of his family ties, Commerce Professor, journalist, director and counselor of El Norte de Castilla, father of seven, faithful until his death to his wife, their “rupture” is not theatrical nor definitive. He is a hunter of minor scale. His safaris last only for one day. At night he likes having his feet wrapped up in his sleepers and read with the warmth of a nice fire in his home of Paseo Zorrilla. He loves routine. He always stays at the same hotel when he travels to another city and if possible he asks to sleep in the same bed each time. He claims that being faithful in him has no great value. But he says all this with some distress by some means. Firmly settled in his city, his family, his friends, in the newspaper he is an intimately displaced. The world that he graps is in a horizontal sense, the province towns and that exotic world that starts where interstate roads end. In a vertical sense he has the upper-middle class and the peasant class. He describes the daily drama of the province towns and the archeological of the rural means.

«Conversaciones con Miguel Delibes»

César Alonso de los Ríos

Madrid, Magisterio Español, 1971, pp. 16-18.

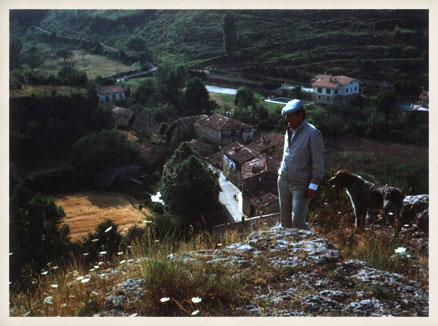

Delibes is a man from its region Castilla and he is proud of it. He moves swaping Sedano and Valladolid. Sedano is a beautiful village in Burgos that has enchanted him. There, in Sedano, Delibes built a retreat for himself in 1959, and there he spends really good times. He keeps on having his house and formal residence in Valladolid and up and then he visits the headquarters of El Norte de Castilla (the newspaper where he spent most of his working days.

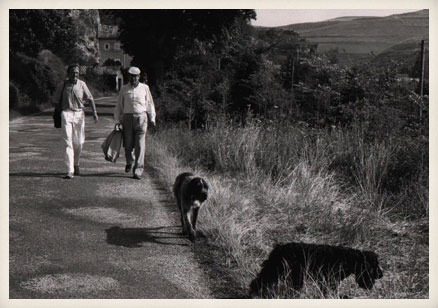

But it is in Sedano where he actually likes living and where this tall, bony, a wide forehead, straight nose, eager eyes (although short-sighted) and a fairly agile body man writes and truly enjoys. It is in Sedano where he happily wakes up to go hare hunting, where he bursts out in happiness after getting his reward when trout fishing, where he goes for long and calm walks under the trees along the river side, where he oves watching the dog run and dribble, where he contemplates the nests and keeps an eye on the wood pidgeons…Where he deeply enjoys chatting with his children (he has seven kids from his marriage to Ángeles de castro, of whom he is now a widower) and playing with his grandchildren ( he has six and they frequently visit him). Sedano is for him the ideal place to keep on falling in love with nature. It is there where Delibes feels more himself.

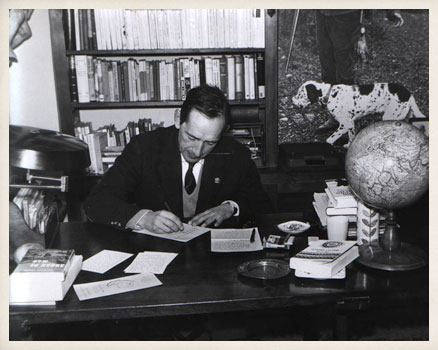

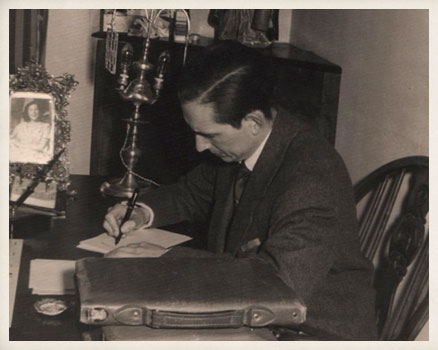

It feels like Delibes likes to maintain this image of a sad and rather pessimistic man. Nevertheless, in the same way that his novels are determined by drama or tragedy a ray of irony sticks out in the human relationships that Delibes portraits with a touch of jolliness and good sense of humor. He is a man that gives off human values, a person of great friendliness and enjoyable conversation. He always has the most sensible answer among the all possible. A peaceful man who rarely hesitates when it comes to give his opinion about any matter. He handwrites his novels and works with the same calmly wisdom with which he speaks. Everything takes its time.

Any type of work to be well done needs a certain balance. Delibes´wokrs have it, they are fortunately, sensible pieces of work as his author is.

«Miguel Delibes»

Manuel Bartolomé

Miguel Delibes, Los santos inocentes.

Barcelona, Círculo de Lectores, 1985, pp. 180-182.

Miguel Delibes with his dog, Grin, in Sedano.

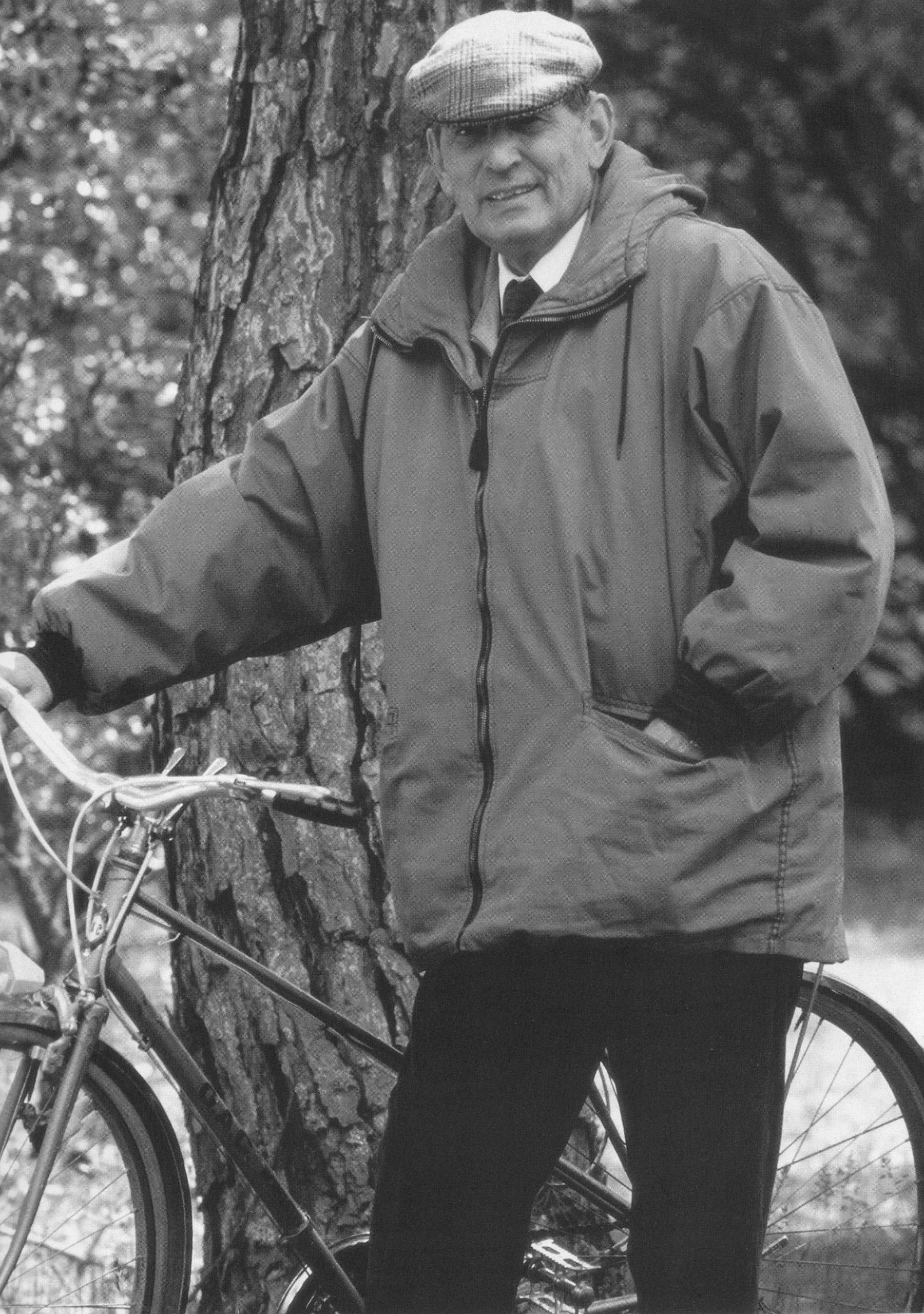

The writer walking through the Campo Grande Park, Valladolid, 2004.

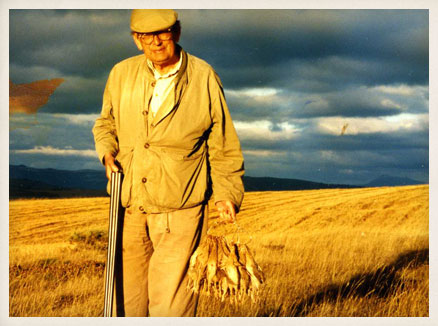

Miguel is a passionate Castillian man who loved birds and the weekends, but once the hunting season was on, he would shoot them to death. His beret, boots, a bicycle across the Campo Grande, a cigarette and a worn out jacket which, gave him the distinction of “most elegant man in Europe” (title shared with André Malraux), a broad wide smile and certain melancholy (the touch of class of the pessimistic).

At the age of ten, the psychology teacher of his school in Valladolid La Salle, said about him: “he has a rather sad and gloomy look, nevertheless, Miguel is the most cheerful and jolly boy of his group”. Miguel, sad and cheerful. He sang: “I was dancing with Lola yesterday afternoon”, meanwhile he chased the red partridge.

He says he is a hunter that can write, not a writer that hunts .He hates aeroplanes, elevators and he seeks the open air of that Castilla which Unamuno named “dermoesquelética”. If Castilla didn´t exist, this man, (descendant of the French composer Leo Delibes lonely and sensitive) could have been happy in the Far West without shooting a single buffalo or Sioux but peharps one or two wild ducks, since he was a merciful hunter. Miguel is merciful and generous, a bit tormented perhaps but very keen on justice and fairness and contrary to faking or exagerations. Sincehis wife died he needs to take sleeping pills to beable to sleep, but another issue worries him too: the world is not the way he would like it to be.

«Fuego y humo»

Manuel Leguineche

El Urogallo, 73 (junio 1992), p. 51.

I was always impressed by Delibes´ coherence. He is one of the fewest men that says what he means and thinks before speaking and he acts according to what he means and says.

«Retrato de Miguel Delibes»

Antonio Giménez-Rico, en Antonio Corral Castanedo

Barcelona, Círculo de Lectores, 1995, p. 97

Nowadays a writer who believes in God is an exception and without a doubt Delibes is a Christian. His faith in God is expressed in his respectful attitude torwards all living creaturesand his strong human values and this is plain to see in his literary style which allows the characters to have their intellectual and linguistic independence.

Even Delibes´ life is an example of stability and at the same time of very deep beliefs in the humanbeings, these two allow him to live within the Spanish society without losing his dignity as a commited man. The life of Delibes is for us a clear example of how an authentic man can live in a historically difficult period of time.

«Miguel Delibes: desarrollo de un escritor» 1947-1974

Edgar Pauk

Madrid, Gredos, 1975, p. 20.

In the true astonishment of Miguel Delibes about the success of his books, his total absence of vanity, is where I find the key of the success of the writer. All of him, pure, real, attached to his homeland, touched by the true humanism… I hope that Miguel Delibes still writes many more books. Wonderful, melancholic books about the people and the region of Castilla; condemming books; books about the love to the sad human nature; books about children, partridges and hares; about the naïve irony of some heart in love. And the reader will claim once again: “this is the best book of Miguel Delibes”. What the reader always said so far. Is such the writer´s strenghth that was gifted with the genious touch.

«Retrato de Miguel Delibes»

Josep Vergés, editor de Miguel Delibes, en Antonio Corral Castanedo

Barcelona, Círculo de Lectores, 1995, p. 95.

Miguel Delibes and Josep Vergés, 1985.

His novel has been labeled as idilic without considering that perhaps it contains more sadness and pain tan the eye can meet. Death is a constanct in his novels from the first one. The plot of La sombra del ciprés es alargada, spins around two key dead characters, and in Señora de rojo sobre fondo gris, where all his rhetoric falls silent, or in those wars of ancestors that are very present, or in the silence of Castilla that is always talkative although it seems quiet and silent. This clasic implacable (death) showed us that there are no possible idyll without unjustice and terrible suffering […]

His name and his work allow to get to know ourselves better, they go through us and illuminate us, without them we would be perhaps poorer, lifeless, less open minded and less human beings. Thus out deep gratitude for his simple accuracy, for being a gentleman and his inner elegance, being so discreet and his amazing dignity that makes the rest of us a little more deserving.

«Miguel Delibes o el rigor»

Rafael Conte

El Urogallo, 73 (junio 1992), p. 45.

I am urgently required to write “something” about Miguel Delibes, to celebrate his latest Cervantes award. It is hard to find the exact and precise words when someone receives such an important distinction, but even harder when the person who receives the award is so deserving […]. Miguel Delibes´ literary honesty goes hand in had with the endearing personality that all those people who had the opportunity to have contact with the writer get to know. His discretion, his sincere modesty his hard working ways and his greatness as a human being have to be doubtless reflected in his narrative work and so it is proven in remarkable work.

Throughout Delibes’ words language adquires a new dimension in his impeccable use of the castellano from his hometown, Valladolid, used with a peculiar spontaneity, and his special elegance and care so characteristic from his writings.

I think Mr. Antonio Machado wrote the biggest compliment that someone could pay to this incredibly honest, sensitive and calm man, and I do think that beyond any futile praising he is “in the best meaning a good man”.

«Tras el Cervantes»

Rafael Alberti

Miguel Delibes. Actas de El Escorial.

Madrid, Universidad Complutense, 1993, p. 193.

Miguel Delibes, Rosa Chacel and Rafael Alberti. San Lorenzo de El Escorial (Madrid), 1991.

First things first, I have to say that I admire Delibes since many years ago and I have expressed that admiration in and outside our country. I believe his work offer an autonomous, personal world with a deep ethic vision, which I consider essential in good literature and in a good command of the language. In my opinion, these requirements make Delibes the first classical author of the contemporary castillian narrative […].

Hereby I confess that I dindn´t have Delibes as a role model at least consciously, when I wrote some of my essays that talk only about women or that can be considered as a monologue, and where I intended to represent the popular language of Mallorca, but somehow now I think that Delibes´ model was behind all these writings of mine. I´m afraid that the involuntary due I adquired with Delibes will be hard to pay back, but at least I expect to give him back some credit by acknowledging his influence and thanking him in public in front of you all.

Also in public, before concluding, I would like to thank Miguel Delibes for some other matters that go beyond the mere stylist aspects of his literary works and that deal with the moral values that in these works defend. In a damaged and gradually less innocent world, Delibes takes care of the nature which he loves, for this reason he is a commited ecologist; he worries about the children. His childish characters are thus unforgeteable: characters like Nini in “The Rats” or Daniel el Mochuelo will walk with us foreve. In a degraded world that eagerly seeks power, and the need of being in the spotlight (including many writers), Miguel Delibes keeps on being a ankor a safe place where we can look for shelter knowing that his style and his personality will never let us down.

«Miguel Delibes, punto de referencia»

Carme Riera

Cruzando fronteras. Miguel Delibes entre lo local y lo universal.

Valladolid, Cátedra Miguel Delibes, 2010, pp. 225 y 227-228

Miguel Delibes is one of those men that surprises you when you meet them in person and they are taller than I had imagined. He was taller and he had a jolly and healthy aspect, with that natural tan of those who spend time in the open air and the minute you started talking with him, that whining image of the photographs totally vanished. Tall and robust, more tanned if we compared him to the paleness of the rest, I saw him once moving across a big room taking large strides, wearing a corduroy jacket, a rather sloppy knotted tie, showing with no reserves his irritation to another of the many scams in the Spanish cultural sphere. He was deeply irritated, but still he kept calm with the impartiality of despair but common sense, because he was a warm-hearted man who I cannot imagine being dragged by the Spanish quarrel or the rough and rude manners that many times people mistake with being brave. Young writers, like me, stopped reading Miguel Delibes´work because he was “too Spanish” and “too castellano” for us, when we were so eager to be cosmopolitans, but the truth is that there was something in Delibes´attitude, in his presence that made him quite distant to the tipical Spanish model to which we were used to.[…]

We abandoned the habit of reading Delibes because were were in a hurry to become anglosaxon writers, but we couldn´t see that he wasa very close in his attitude to an English or American novelist. Miguel Delibes lived in his retirement writing and having long walks in the nature. He was a writer because he wrote books and not because he played the public persona or writer according to the Spanish, French or Latinamerican style [… ] Maybe if Delibes had been more likely to fall into arrogance, we would have paid more attention to him. But he didn´t even had a legend […]. He lived in Valladolid working as a civil servant and being a father of seven. Old age and illness turned him discreetly into an invisible man.

«Delibes, a lo lejos»

Antonio Muñoz Molina

El País, 20. 03. 2010.

DELIBES

The journalist

I was born into journalims fourty years ago and throughout El Norte de Castilla and my occasional colaborations with other newspapers and magazines I kept my bond with this profession along four decades. During this time I learnt two essential for my later dedication as a novelist: consideration for the daily life events-those the press expose-and the summarizing requirements that nowadays journalism needs to expose facts with the largest details that involve those facts but expressed with the smallest number of words. With this previous experience in journalism I rolled into narrative and even the years have passed by, I keep on sticking to those rules, in other words, my novelist condition leans on my journalist condition. Journalism has been my narration school.

Carta-prólogo a Estudios sobre Miguel Delibes.

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Universidad Complutense, 1983, pp. 9-10.

Numerous articles […] and half a docen of travelling books are the clearest example of his condition as a journalist and reporter. […]

There is also in some of his novels a clear literary use of his journalist resources. Just a few examples to be rememberd are those pieces of news that are shown at the beginning of some chapters of Mi idolatrado hijo Sisí or the texts with which Mr Eloy teaches how to read Desi in La hoja roja, that are also newspaper headings. The obituary with which Cinco horas con Mario starts, is in itself a journalist text and in Diario de un emigrante, that has as an inspiration a trip that Delibes made to Chile and that collects a numerous amount of resources that the writer previously used when he published his travelling chronicles in the newspaper El Norte de Castilla and later he gathered in his first travelling book. Cartas de amor de un sexagenario voluptuoso is somehow a chronicle of the difficult situation that the Spanish press was going through during Franco´s regime. Apart from the creation sphere, the Spanish press situation during those years is the main essay topic in “the censsoship of the press during the 40’s”.

Claves para leer a Miguel Delibes, Siglo XXI

Amparo Medina-Bocos

Literatura y cultura españolas, 3 (diciembre 2005), p. 166.

Miguel Delibes was not like many others just a writer who published articles on the newspapers, he was truly a professional journalist. He started very young in this business, just in his twenties; In the beginning of 1941 as an occasional draftsman for El Norte de Castilla and then as an editor. Later on he became the assistant manager of the newspapaer, the oldest newspaper of Spain and finally he became the manager. This means that Delibes doesn´t limit himself to the mere journalistic production for the press, even if it was plentiful and varied. He goes beyond all this, he covers all the structural framework of the functioning of the newspaper, even making difficult decitions, especially when he was the word of command of the newspaper, that had significant consequences in the editorial and the business path of the newspaper.

[…] the novelist belongs to his geography and his time, to his circumstances. In the case of Miguel Delibes, journalism was more than a circumstance or a life style. It is true that he was never exclusively dedicated to the journalism. First he combined journalism with his preparation for the official exams to obtain a position as a professor in business law at the Business School of Valladolid. Afterwards whe he obtained the mentioned position in 1945 he balanced journalism with his job as a professor. And finally from the year 1947 onwards, especially when he received the Nadal award, he combined journalism with his dedication to literature. These three facets- teaching, journalism and literature-coexisted together in some other people, but never with the implication and the excellence that Delibes achived in each of those facets.

Prólogo a Miguel Delibes, Obras Completas, VI. El periodista. El ensayista..

José Francisco Sánchez

Barcelona, Destino-Círculo de Lectores, 2010, pp. XV-XVI.

Miguel Delibes with the novelist Luis Berenguer and part of the writing team of El Norte de Castilla (J. J. Rodero, Jiménez Lozano, Carlos Campoy and Emilio Salcedo).

Delibes was determined to form a team of collaborators to whom he only required a good cultural formation and the willingness to intervene in society. He didn´t care about political positions or possible compromises. Delibes and that group of collaborators- Lozano, Umbral, Leguineche, Pastor, Pérez Pellón, Arrizabalaga, Gavilán- and some editors like Félix Antonio González and Campoy, were a lucky team in those constricted years. He placed himself in the position of the narrator and placed us in the palce of the intellectuals. The most important thing is that he encouraged us to speak our minds. He was just the opposite to the censorship regime.

To me Delibes has been a very significant figure. Not only because he guided me to journalism, but also because he taught me the hard lesson of putting to the test and how to recognize the other´s reasoning. A radical liberalism that has nothing to do with the dogma of economis and political liberalism. I learnt from him, that we need to be intelligent pessimists and willing optimists. Delibes has been for me an ethic reference. It is my duty to claim now that when I was arrested and processed in 1962, Delibes doveted himself totally to my defence. He felt that swipe on his own skin.

Delibes: periodismo y testimonio, en Miguel Delibes,

Premio Nacional de las Letras Españolas 1991.

César Alonso de los Ríos

Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura, 1994, p. 111.

Francisco Umbral

El País, 7. 05. 1984

Miguel Delibes with Francisco Umbral and Manuel Leguineche.

Delibes persuaded me, Paco Umbral and many others from applying literature to journalism. From his manager desk at the El Norte de Castilla, he initiated me in the secrets of his life and work, the simplicity, the common sense, the truth, being natural because everything that is fake is not good. He taught me all this, without patronizing me, he did it his way, without being annoying, without using aggressive language, with his well-intentioned irony, just with pure and subtle suggestions. Miguel managed the newspaper as the good referees lead a football match. His managing was not noticeable. Beside him we collected the multiple sounds of the news, the symphony of the sports, the municipal chronicle, the reference of the cabinet that always came in late throughout the Teletype, the local chronicle, the throb of the agriculture, the theological beating of ´pepe Lozano. Miguel created a brand new section, “El caballo de Troya”, which resulted rather irritating for Mr. Manuel Fraga. The discourse of the Minister of the movement has to be layed out in four columns. We had to sort out instructions such as “To its mandatory publishing hereby I send attached…Note related to the National Contest of Music Bands that will take place in Murcia”.

Fuego y humo.

Manuel Leguineche

El Urogallo, 73 (junio 1992), p. 50.

Being the Manager Director of the newspaper was a hard position for Delibes. This hard work had several stages: an internal management during two and a half years, full time management interrupted by the election of a responsible assistant manager, another stage of highly controlled management, going back to being the manager director and finally becoming a delegate of the editorial department at the board.

The detailed analysis of the circumstances, of these declines and relapses and above all the reasons of Franco´s burocracy is at this time is quite disappointing and somehow humiliating.

It is clear to see Delibes´ struggle to inform specially about the situation of the fields of Castilla and the agricultural problems; his attempts to introduce collaborators who were not linked to the regime, his disgust towards the subjugation of the instructions of the editorial page; his effort to be up to a society which wants to get rid of the authority of that regime […]

On the other hand, in this long process, the unity of the Administrative Board of the newspaper starts to break up due to the clash between the liberal tradition of the newspaper and its sales and the new collusions with the regime spaecially when Fraga came to power. In this way, what it had benn a strong support for so many years, turned into an ambiguous atmosphere which brought painful personal problems to Delibes.

Delibes: periodismo y testimonio, en Miguel Delibes,

Premio Nacional de las Letras Españolas 1991.

César Alonso de los Ríos

Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura, 1994, pp. 102-103.

Those years were as matter of fact, a period of time when we had to pay attention to the subjects, verbs and predicates, but we also ha d to learn how to enphasize, keep silent and deal throughout the language in some areas of the newspaper […].

“The room of the draftsman” received that name because in previous years it was in this room where the draftsmen of the newspaper udes to work, and from those years there were remainings of a big old desk and a cork panel that afterwards became half a notice board and half a panel to pin there cut outs and interesting things. At the back there was a sort of bookshelf which one door could be bent over and could be used a a desk to, ther was where Delibes installed himself and made his working place when he abandoned his Manager office: that became, as I like to call it, his grammar trench. There everything could be told as if it was a novel: the plot and the characters were always fighting for supremacy and then the eternal dilemma of how to say or not to say; saying not to say, how to insinuate without giving the feelling that it was an insinuation and how to spin round and round without ever landing but giving the sensation that you were touching the ground, or sometimes simply hit the bullseye. There was really nothing more stupid that the rules of a prining house- it doesn´t matter the name that it has- but maybe there nothing better than that to really learn what language means and no one better than a writer to teach that sometimes you can target one objective and hit a completely differnet one and it still will be real.

La habitación del dibujante

José Jiménez Lozano

El Urogallo, 73 (junio 1992), p. 48.

It is not difficult to check that Delibes feels at ease in some certain topics that he rarely abandones […]: Castilla and its people, Literature but moere specifically, novels, Nature- in which we could include his two favourite sports: hunting and fishing- and his memories of his Friends. It is evident an almost total absence of of political or ideological topics, except the Chronicles he send from Chzec Republic (La Primavera dePraga, 1986) for the magazine Triunfo […].

In general, Miguel Delibes does not incide in his heading on the so called important topics with only a great exception which will be those concerned to the Education issues. Normally he preffers “minor topics”, domestic issues and above all he prefers human beings themselves- also close, routinary too- as the topic for his articles. Delibes used to say of the art of writing novels that. “The narrative art leans no so much on being original, but on the importance of those aspects that seem unimportant, using for this pupose the description of characters with consistent and human qualities”.

El periodismo de Miguel Delibes

en Nuestros premios Cervantes. Miguel Delibes.

José Francisco Sánchez

Universidad de Valladolid-Junta de Castilla y León, 2003, pp. 76-77.

DELIBES

The narrator

In my opinion writing novels is in a way telling a story. For that purpose it is necessary the help of several elements: characters, time, construction, focus, style. As I see it, with this elements we can create as many experiences as we like… all the experiences, except destroying them, if we did then we would be destroying the novel. There is a wide range of experimenting possibilities, with only one limit: that something has to be found.

César Alonso de los Ríos

Conversaciones con Miguel Delibes.

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Magisterio Español, 1971, p. 143.

I give my characters an outstandig position above all the elements that are combined in a novel. Characters that truly become alive make the arquitechture of the novel be in a secondary position, they make of the style a vehicle which existence becomes merely an anecdote and they can make realistic the craziest plot.

Un año de mi vida.

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Magisterio Español, 1971, p. 143.

I transfer to my characters all the issues and distress that hassels me, or I show the thoroughout their mouths. This is, if the author is sincere, he or she reflects him/herself in them.

César Alonso de los Ríos

Conversaciones con Miguel Delibes.

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Magisterio Español, 1971, p. 143.

From my point of view an authentic novelist nourishes from the observation and from inventions as much as he nourishes from himself. The authentic novelist has in him not only one but hundreds of characters. Hence the first thing a novelist should do is to observe his own interior. In this sense all novels and all the main characters of a novel have inside of them a lot of the author´s life. Living means a constanct choice between several alternatives. But when it comes to face the blank papers, the novelist must have the skill to direct his own life towars a different destination that perhaps he previously rejected. This means that the novelist can imaginary recreate himself. So, we can conclude that above the novelist skills of inventing or observing, he must have the skill of splitting himself: I am not this way, but I could be this way. In other word he has to be able to give testimony not only about what it really happened, but about what it could have happened in each possible case and situation.

Un año de mi vida.

Miguel Delibes

Barcelona, Destino, 1972, pp. 92-93.

For me the hardest task of a novelist comes before the creation part, before he starts to créate literatura itself, this means, when he has to plan the topic of the book and try to find a way to develop it and resolve it.

César Alonso de los Ríos

Conversaciones con Miguel Delibes.

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Magisterio Español, 1971, p. 132.

Each novel requires a different style and a different technique. You cannot tell the story of the problems of a folk that lives in agony (Las Ratas) in the same way you tell the story of a man ditressed by mediocrity (Cinco horas con Mario). The first task of a novelist, once he choses the topic of the novel, is to find the correct formula to tell the story and the second task to find the appropriate pace […] Whenever those problems are solved, the creation temperature-that some called muse and some other inspiration- cannot be denied. In that precise moment the tools of the novelist to eliminate unimportant details play a big role. By this I mean that once you are in possession of the formula (technique) and you got the right pace (style), the difficult thing is not to write a long novel, but to say what we inted in the shortest number of words possible.

Un año de mi vida.

Miguel Delibes

Barcelona, Destino, 1972, pp. 97-98.

The novel cannot remain anchored in its same old purpose of entertaining the upper-middle class, but I think that there is more interest in deep innovation than in formal experiments. Nowadays, the novel, more than entertaining – we already have commercial films and the television for that purpose- it should disturb, disquiet. The novel is perhaps the most direct instrument we have to drill that arrogant certainty of a self satisfied upper-middle class.

Un año de mi vida.

Miguel Delibes

Barcelona, Destino, 1972, pp. 134.

Our mision is to criticise, bother, condemn, sting the actual and the future system because all the systems are liable to be improved and this, as I see it, can be achieved only from a free conciousness not attached to any specific political stream.

Un año de mi vida.

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Magisterio Español, 1971, p. 99.

Delibes conception of the novel is based on a total rejection of innovation just for the sake of it. It is also based on a strong support of the narrative that refers to a story. That theory was formulated by Delibes himself in various occasions and it focuses both in the form but also in the content to explain that form can only occur if content is appropriate, and viceversa. In his own words: “I have to praise any form of the novel as long as we take into account that the form, regardless what form it is, has to be necessarily filled with something”, “The most important thing in a novel is what is being told, how it is told, could never crate a great novel, even I would dare to say, that could not even create a novel”. Delibes therefore, strongly support a type of novel that contains events. The readers keep on asking for a character, a landscape and a passion.

Hora actual de Miguel Delibes, en Miguel Delibes.

El escritor, la obra y el lector

Santos Sanz Villanueva

Barcelona, Anthropos, 1992, p. 85.

Miguel Delibes is a novelist in the sense of Proust, Tolstoi… He takes more interest in social psychology than in social structures. For this reason he is so important for me not only as a reader but also as a historian. The novels of Delibes are a rich and endless source of historical documentation to reconstruct the recent past of this country. In particular the post-war period and all related to the upper-middle class of the provinces.

I´m not underestimating the importance of the sources that we have as historians, but estatistics, for instance, are only the skeleton, a scaffolding. A historian has to add sking to those bones and for that purpose there is nothing better than the support of a novel. Cinco horas con Mario, Mi idolatrado hijo Sisí, only to mention some titles, reflect better than any aseptic report, the province post-war life in Spain. The authentic History is found in how people used to live, not in figure. Delibes openly shows, with his irony-making a good use of Literature, that is for sure- the moral schizophrenia and the snob and fake attitude of the early upper-middle class during Franco´s regime.

La sociedad española de posguerra en la novelística de Miguel Delibes, en El autor y su obra: Miguel Delibes.

Actas de El Escorial

Raymond Carr

Madrid, Universidad Complutense, 1993, p. 69.

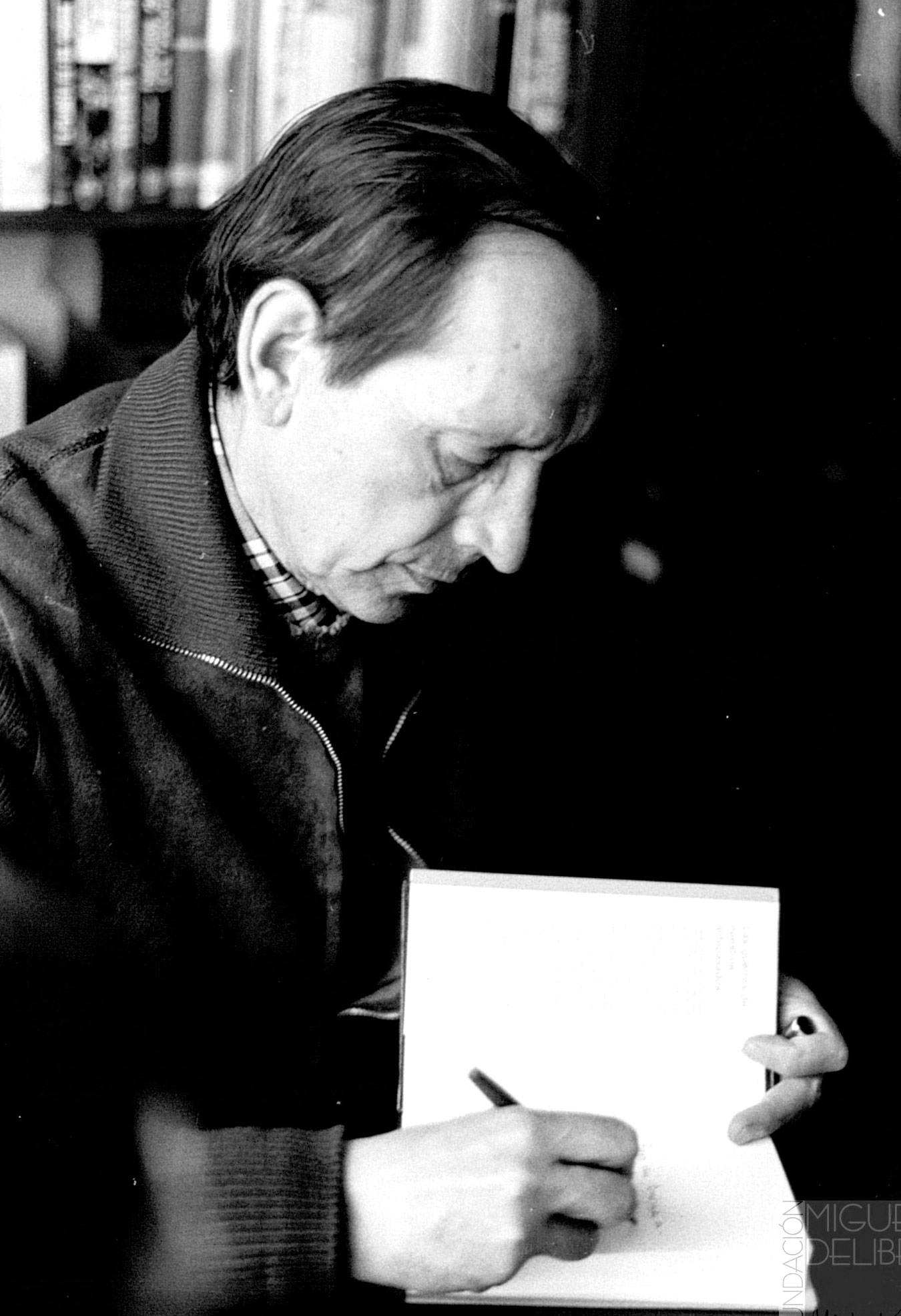

Miguel Delibes signing copies of his books. Madrid Book Fair, 1990.

In my novels, I eagerly try to cover the totality of the region where I was born and raised and where I live, so I couldn´t dismiss any of its landscape expressions and thus in “El Camino” I pay tribute to the Mountain, Iguña Valley, where my family roots are, in “Las ratas”, “La hoja roja”, “Diario de un cazador”, “La mortaja” and “Viejas historias de Castilla la Vieja”, I portray the vast inmensity of the fields in Valladolid, Palencia and Zamora, to the North of the river Duero; and finally in “Las guerras de nuestros antepasados”, “El disputado voto del señor Cayo”, “Parábola del naúfrago”, “Aventuras y deventuras de un cazador a rabo” and “Mis amigas las truchas”, there are a great variety of descriptions of the abrupt intermediate region of the north of León, Burgos, Palencia and Soria, perhaps those are the regions in Castilla that are less considered in Literature, although those regions are not less besutiful. Those regions shor great heights and peculiar vegetation that introduce the Northen lands combining with extreme wheather conditons and the deep blue sky so tipical of Castilla.

Castilla, lo castellano y los castellanos..

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1995, p. 26.

The narrative technique of Migule Delibes is of a high plasticity: throughout the words “you can see”, you can feel the human characters and the atmosphere.

Eduardo Haro Tecglen

El País 28. 11. 1979.

In my novels and short essays about Castilla I only intend to be precise and to the point. Those who accuse me of having an excess of literature in my novels are wrong, and they rarely have visited the villages of Castilla.

Reading Garrigues has led me to a rather accuracy tendency which becomes more noticeable when I started dealing with the inhabitants of Castilla. This is, the precision with which they address their problems or the fact that the lay of the land that sorrounds them is quite unusual, peculiar. This rural language- that has nothing to do with popular language- still keeps on catching my attention.

When I write in my books “cabezo” or “cotarro”, they don´t mean the same. These kind of things are known by people from the villages but perhaps not by people from the cities. The Cotarro, teso, cueto, are not cabezo. The cabezo is simply the cueto, cotarro, the hill that presents a mount crest of holm oak trees. This language could seem picky, but this is accuracy.

César Alonso de los Ríos

Conversaciones con Miguel Delibes.

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Magisterio Español, 1971, pp. 183-185.

The most characteristic feature about Delibes, the thing that best reveals his narrative is his way to take into the novels the point of view, the creation from inside of a principles system and beliefs of his characters. In other words, Delibes constructs character novels, his way […] The originality of Delibes leans on placing his characters in the center of his novels […] Many of Delibes´characters are normal and modest people whose lives don´t experience anything worth being told. Mochuelo goes to school, Nini prowls around in his village, Lorenzo gets married and goes away, Carmen does the household chores, Quico gets bored. What is being told are the combination of daily routines which lack epic importance […] The greatest temerity of Delibes is to make worth telling in an artistic way what is consider unimportant, and this means making a novel spin around a simple character to whom nothing intereting happens […] An essential aspect to understand the mos characteristic novels of Delibes is the perspective from which they are told.

The narration in first person arises from the need of the main character to tell what happens and to show his/her vision of the world […] The same pattern is followed in those novels in which a simulation of first person narration exists as in El camino, Las ratas or El príncipe destronado, in these novels there is not apparently a main character able to support the weight of the narration, for this reason a narrator in third person is necessary to cover up. So, then we know how the miracle of language happens in these novels: the language of the narrator is leaked through the language of the characters, and the characters end up imposing their vision of the universe […] In Delibes´novels happens that perspective is one of the ingredients of reality.

La originalidad novelística de Miguel Delibes.

Alfonso Rey

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, 1975, pp. 259-275.

This reflection about the linguistic porosity of Miguel Delibes takes us in a very unexpected way to the key of his novelistic formula, or at least what for me is: an extraordinary way to “give voices to characters”. Delibes can create the voice of a village child, the voice of a rude housemaid, the voice of a snob young girls of the capital, the voice of a hick a redneckof Castilla with such an efficiency that becomes his greatest virtue when he creates novels. This talent of “giving voices” is not not only about reproducing exactly the voices of folklore, but also is about having the capacity of giving the narrator of his novel a “neutral voice”, but with a slow witted saying tone that matches very well with with all his charactes in general but not having a special attachment to any of them. […] Delibes does not intend to fill his novels with popular voices or dialogues, for this reason he also speaks like another of his characters in the novels.

Miguel Delibes.

Francisco Umbral

Madrid, Epesa, 1970, p. 63.

If pity gives the entire work of Miguel Delibes an ethic density that is constanct, his art could be defined essentially as rhythm: catching the human melody in repetition and variation. Every novel or narrative work that is considered to be poetic in itself and merely informative, has a rhythm that can be noticed at all levels: sentences, characters, events or situations, expansive symbols, interwoven topics. But there are novels and tales that dissolve or soften the rhythm, and other make it harder or more tense. Delibes´ narration belongs to the second group: words are repeated, sentences, features, situations, motifs, images focused on highlighting some symbols that give the special tone to the text and make wider the meanings, also some topic aspects are repeated to create a whole full of intentions.

Prólogo a La mortaja.

Gonzalo Sobejano

Madrid, Cátedra, 1987, pp. 44-45.

The best novels of Miguel Delibes exhale an almost painful brithness in which the beauty of the natural world and dispair of the innocent are very frequently desecrated by fatality that chases those who doesn´t have anuthing, by brutality of the strong, by the changing of times that drags everything the good and the bad[…]. What we find in the great novels of Miguel Delibes is not of costumes and manners but careful observation of the human lifes and the jobs and the dreams of ordinary people; he pays equal attention to the names of things and animals and plants as for the speaking details […]. Perhaps there is nothing more difficult for a novelist than the task of looking at the world with the eyes of a novel character and so leaving aside his own voice and transcribe to the text a different voice to his. In the contemporary Spanish novel there aren´t more truthfull looks or voices than those of the creatures invented by Delibes: a boy scared of feeling the adulthood so near, a poor housemaid, an institute janitor keen on hunting, a mentally retarded man, an old man that sees how the end of his life comes nearer, a province wife who lives in anger. In Los Santos Inocentes, the story, the language, the point of view, the depth of the consciousness they all melt and transform in only one narrative stream only interrupted by the rhythm and poetry written in prose.

Delibes, a lo lejos.

Antonio Muñoz Molina

El País, 20. 03. 2010.

DELIBES

And nature

Probably you may have observed that the birds, those little creatures for which I feel a special preference, become quite frequently important characters in my books. Diario de un cazador is full of partridges, quails, ducks, turtledoves and doves. “Viejas historias de Castilla la Vieja” is full of great bustards, rooks and bee-eaters. The great duke is an essential piece in “El Camino” as the picaza is also essential in La hoja roja. The eagels, the kestrels and camachuelos are part of the environment of the little Nini in “Las Ratas”… Finally in my two latest novels, “El disputado voto del señor Cayo” and “Los santos inocentes”, take part three birds that play essential roles: the cuckoo and the rooks in the first one and the rooks and the cárabo in the second. Of those three birds I make my tool to compose the book that you now have in your hands, it is not a book of tales or invented stories, but a book of real stories, stories that I lived, stories in which those birds are the real protagonist. I hope that reading them doesn´t leave you indifferent but on the contrary they arise in you the love for nature.

César Alonso de los Ríos

A mis lectores, en Tres pájaros de cuenta

Miguel Delibes

Valladolid, Miñón, 1982, pp. 4-5.

Whether we like it or not, human beigns have their roots in nature and by uproting us with the lure of technology, we have deprived ourselves of our essence […] Fromm y Castilian retreit, or what is the same, my personal experience, these are the kind of issues that I tried to portrait in my books. We killed the fields and land culture but we haven´t substituted it with nothing, at least nothing worthy or honorable.

And the destruction of Nature is not only physical, but also a destruction in its meaning for humankind, a truly amputation of the spirit of human beigns. Purity of air and water is stolen from human beigns but also it occurs an amputation of their language and the landscape that is full of referencing and characters and that conforms their comunity in which their life takes place, all this is transformed into a depersonalized and meaningless environment.

In the first of these aspects, how many are words related to Nature and that right now they are already obsolete and that in a few years time they will not mean anything to anybody and they will become just a bunch of words buried in dictionaries and they will be unintelligible for Homo Tecnologicus? I´m afraid many of my own words, words that I use in my novels set in a rural environment, for instance, aricar, agostero, escardar, celemín, soldada, helada negra, alcor,( just to cite a few) they will soon need of translation footnotes as if they were written in an old fashioned language, when the truth is that thet only try to reflect life in Nature and the life of men and women that live in Nature and give name to the landsacape and animals and plants with their authentic terms. I think that the simple fact that our dictionary omits many names of birds and plants that are of common use in the rural life is a sufficient indicator of this aspect.

S.O.S. El sentido del progreso en mi obra

Miguel Delibes

Barcelona, Destino, 1976, pp. 76-77.

Peasants often use femenine, tender and softer and even more maternal terms and words than those used in dictionaries or by people from the cieties to name trees and birds. In cities or dictionaries the masculine term are prevalent .This understanding human beings-animals, human beigns-plants is plain to see in all my work that is full of partridges, hares, foxes, dogs, rats, goldfinches, roosters, doves, magpies, trouts..and also full of trees and bushes in such way that it is enough to open any of my books, even those of more urban topics to prove that those elements are constanct in me.

Humanización de los animales, en Castilla, lo castellano y los castellanos

Miguel Delibes

Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1995, p. 108.

Reading Delibes goes beyond literary referencing even if it is literature what he offers us. The fact here is that he is a novelist, as if we walked with him his hunting routes or around Sedano in Burgos, he invites us to stop in front of a scrub or at a small valley or hill, stop at a erode gorge or a flying partridge and a rabbit that starts to run away or an old man that has a little nap under a quince tree, perhaps without any memories and empty toughts.

The landscape is alive and in it you can feel the beating of the surviving passion of the protection from the scorching hot winds or the northern cold that sometimes will leak through bringing cold winds that frequently mean bad omen.

The land is full of life and it only needs of some eyes that reflect its beating heart and that is exactly what the books of Delibes offer.

Miguel Delibes

Emilio Salcedo

Valladolid, Junta de Castilla y León, 1986, p. 60.

After the spectacular cultural change in this quarter of the century, Delibes appears as a man advanced to his time. “In some way and without being conscious about it, I came to be a precursor that sensed the risk. When I wrote “El Camino”, in 1950, a critic observed that I was reactionary because the protagonist of the novel was a person who loved his village and refused to become part of the caos of the great city. Fourty years after, in a public event, the Minister of Culture, presented me as the first ecologist of Spain because of that book. What could have happened in the world only in four decades that two people could give such different judgemnts of the same writer? In Spain occurred the falling apart of the rural world and an exodus from the vilages to the great cities, and in the world a progressive damage and decline of the environment”.

César Alonso de los Ríos

Introducción a Conversaciones con Miguel Delibes

Miguel Delibes

Barcelona, Destino, 1993, p. 16.

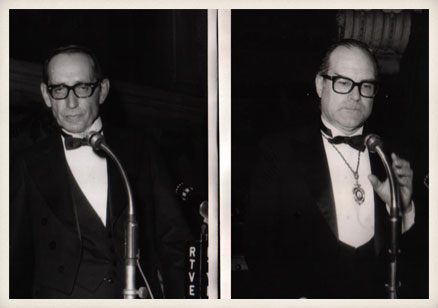

Miguel Delibes and the academic Julián Marías, Royal Spanish Academy, May 25, 1975.

When he had to decide the topic for his first dissertataion at the Academy that todas hosts him, Delibes has rather opted for what he has called the third tendency of his literary work, social preoccupation, anguish for the dangers that threaten Nature and the spontaneity of life in Nature.

Delibes reflects about the fact that almost all his written works have focused on the idea of progress; he has been eager for it but also he ahs feared it; but above all he has not been totally convinced that the term “progress” was accurate for all that has been so called, or also the idea that progress does not necessarily mean destruction of many valuable things.

These worries that come from his love to Nature and to the simpler forms of life, are to my eyes very noble worries and I totally share them.

«Contestación» al discurso de Miguel Delibes en el acto de su recepción en la Real Academia Española.

Julián Marías

Valladolid, Miñón, 1975, pp. 75-76.

It is not a strange thing that Miguel Delibes paid special attention to these matters that he treated with such simplcity and afection on the day that he became a member of the Real Academia de la Lengua (I was lucky to witness this day). He also didn´t hesitate to radically conclude with that theme of an old song: “If the world doen´t chage, If the world is not respected, let it stop so I can hop off from it”. This was a simple but very radical formula to say how much meant to him all along his life his live for Nature and how he values and respect it. The writer could have chosen othe topics, perhaps more specific for instance his own narrative, but he preferred paying more attention to environmental issues that back then were not so dangerous as they are today.

With that message, Delibes´work was becoming universal because we all already knew that he was not referring anymore to the natural areas of his homeland but to the natural areas of the whole planet. In this way, we can say that the writer from Castilla was somehow advanced to his time in the vision of those issues that today- perhaps too late- all the political parties have in their electoral programmes.

«Los libros del corazón, los libros de la vida», en Luces, trazos y palabras.

Homenaje artístico-literario a Miguel Delibes

Antonio Colinas

Universidad de Valladolid-Cátedra Miguel Delibes, 2007, p. 28.

On the 25th of May 1975 Delibes gave his accpetance speech when he became part of the Real Academia de la Lengua Española. I was at that “high auditorium” (as Miguel Delibes called it once) and I still remember the amazement that invaded me when I heard his words. Those were, for sure, difficult times.

The murder of Carrero Blanco had propelled the events and unchained the language or¡f terror in Spain where ETA and other terrorist groups attacks where inmmediately fought back by the extremist right wing and by the hardest of the police repression.

I don´t really know what was I expecting when Delibes began his speech. I guess I though Delibes would evade all those matters talking about nature in his work awaiting better times. Soon I found out that his discourse was nothing but evasive, he would alert us about a more important kind of crisis than that that the Spanish people were inmerse in. The group of Spanish people that were in the Academy´s hall room at that very moment worried about Spain´s fate. But Delibes was talking about human kind´s fate as if our worries regarding our own country were unimportant compared to the upcoming catastrophe that was upon human kind.

In his speech at the Real Academia, Delibes referred to the reports of the Club de Roma. They were reports made at the very first meetings of scientist from all over the world to face what today we called “climate change”. The chages that the environment is suffering due to the human action on the Earth´s biosphere. Delibes had an excellent councellor, his own son Miguel Delibes de Castro, a well known biologist who would become his professor in this phase that started with this speech and cocluded in the year 2007 with “La tierra herida”.

Miguel Delibes. Una conciencia para el nuevo siglo

Ramón Buckley

Barcelona, Destino, 2012, pp. 205-206.

Almost thirty years ago in my aceptance speech at the Real Academia de la Lengua, I took advantage of a very intelectual audience to express my anguish about the Earth´s future. That discourse ended up becoming a book called S.O.S as a first title and then “Un mundo que agoniza”. Even the time has gone by, my worries about the environment have not diminished, but just the opposite. Anybody who paid attention in the last ten years to my words and my public interventions, or read my fishing and hunting chronicles can prove it. The abuses of the people on Nature have not only become less but they have dramatically increased, resources used up and running out, pollution, shortage of fresh water, extinction of species…Some worrying issues that did not exist on the seventies have now appear new: the slimming of the ozone layer and climate change.

Regarding climate I should say that as a man of Castilla and a man of the countryside I have been always interested in that matter. I have pent great part of my life in the fresh air among farmers that surrender themselves to the weather will; men and women whose survival denpend more on the drought, hail or icing frost than on their own effort and work. What would it happen to us if the climate changed? And how would that change happen? I often vaguely read about the Earth´s global heating , but it was after the summer of 2003 ( a living hell that lasted five months), July of 2004 cought me in Sedano, a small villae in the North of Burgos, with temperatures of 2 and 3 Celsius on the plains and maximum temperatures of 25Celsius during the day. “This is not what we agreed” I said to myself. I had not forgotten the heat of the previous summer with almost 50 Celsius in the South of the country. At that moment I saw it clear that the climate change was not a mere theory but something real. It was not the time to come up with theories since the threat had become true. But the, what did that cold weather mean a year after? Maybe my fears where baseless? If the evidence that justified climate change did not adjust after twelve months, why was that rising and decrease happening in the temperatures?

Under those circumstances I took advantage of one of the visits of my son Miguel, to consult him my questions and doubts. I asked him some questions linked to each other but in a relaxed way, nevertheless I guess faking didn´t worked so well and my questions revealed my deep preoccupation. His answers were so extense and detailed that in some more than twenty minutes we had engaged in an extremely passionate and revealing conversation about the future of the Earth. At the end of that morning I managed to convice Miguel to extend our conversation and even more to try to make it public and give some publicity to it since I considered essential that the inhabitants of the Planet got to know the opinion of the scientists about the situation that the Earth is going through. What can a scientist say to a person like me that I am somehow ignorant but worried? The reasoning of the experts are soothing or on the contrary enough to increase our preoccupation? And there was something else, if the problems were real, Why aren´t they getting propper solutions?

La tierra herida,

Prólogo a Miguel Delibes y Miguel Delibes de Castro

Miguel Delibes

Barcelona, Destino, 2005, pp. 7-9.

Delibes’ concern for nature cannot be separated from the his worries about the specific situation of the land where he was born and where he lives, in which landscape he sets the majority of his books and become a central topic of a couple of them; […] “Viejas historias de Castilla la Vieja”[…] and” Castilla habla”, in both cases the main characters of a daily existence in Castilla talk about an unstoppable decline.

Fiction or reality […] inventing or document, in all the books mentioned [ “S.O.S.”, “Vivir al día”, “Mi vida al aire libre”, “Pegar la hebra”] and in some other that we could add we can witness the author´s enthusiasm for Nature, it is so intense that he proposes an intimate communion of the human kind with Nature to trnasfor it in their existing reason. That loving respect for Nature comes not only from his extensive narrative about it but even more from his direct contact with the land and his intense experience about the lands of Castilla, to sum up, all those aspects come from a keen attitude to live in the fresh air, the sport practice in “Un hombre sedentario” as Delibes called himself. His keen attitude to different sports, represented in “Mi vida al aire librw”, such as football, ciclying, swimming, marching…and among all of them to two sports in particular: hunting and fishing.

Memorias de un cazador

en El último Delibes y otras notas de lectura

Santos Sanz Villanueva

Valladolid, Ámbito, 2001, pp. 62-63

DELIBES

The hunter

Hunting is above all a dynamic entertainment sport. Hunting is based on harsh early wake ups, rough walks, cold meals in an inhospitable nature, rain and cruel frosting… But there is something that compensated that hunter in all those adverse conditions. […] A possible catch is enough to diminish all the dirturbing annoyances and to give the hunter a deep mental reward. […] Hunting is more than an entertainment, it is a passion. […]

Hunting is a returning pleasure. During six days a week men get enough reasons to get rid for a few hours of the social conventionalisms, of the daily routineand the predictable. On the seventh day, he gets full of oxygen and freedom, faces the unexpected, experiments with the illusion of creating his own fate…but at the same time he gets tired, is thirsty and hungry and he gets cold… In other words, he finds enough reasons to abandone his primitive experience and go back to his urban, domestic and comfortable lefe. This method is as good as any other to bear life, or maybe even better than any other method.

Prólogo a El libro de la caza menor.

Miguel Delibes

Barcelona, Destino, 1964, pp. 10-11 y 17.

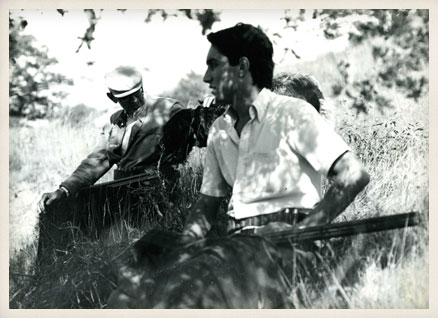

Delibes who is a highly methodical man, had the sense of humor during half a century to note down in several samll note books, with lovely hand writing all the details about his hunting excursions, in those note books there no date before 1949, quite surely because his excursions were few. Also is quite likely that the intensive preparation for the public examinations for the post of professor of business law, had something to do with the absence of notes about his very few hunting excursions as well as his incipient relationship with Ángeles, his wedding and the birth of his first few children.

Once again the unpublished notes of his note books, and also indirectly, the testimony of Lorenzo, the main character in Diario de un cazador (sometimes it was said that Lorenzo is an alter ego of Delibes), reveal that his fondness to hunting had come back during the following decade. Since then his writing about fishing and hunting kept on naturally flowing from his feather pen to conform these important collection of pages […] that collects eight booksand two minor written works that appear between 1963 and 1996. […] These works analyse the hunting world from different perspectives from the motivation of the hunting act to the regulations that control its practice and the analysis of its different modalities to the daily experiences of the author- and that when it comes to its creation, as Delibes himself has admted, mean for its spontaneity, a liberation of the rest of conditions that rule the rest of his literary production, for this reason the author preferred to calle himself “ a hunter that writes” more than a writer that hunts.

Cuatro décadas de caza con mi padre

Prólogo a Miguel Delibes: Obras Completas, V. El cazador

Germán Delibes de Castro

Barcelona, Destino-Círculo de Lectores, 2009, pp. X-XI

Miguel says that he loves minor hunting. Big animals, with their almost intelligent look in the eye, have never been and objective for him. I belive that, in reality, hunting is another aspect of his implication in the rural life that we cannot underestimate. He is in some way a countryside walker, a long distance thinker that uses his shotgun as an excuse to walk and wander around, and think in his own things. “I cant think if I´m not walking” he states, making of this affirmation a moto of some words in Las confesiones de J.J. Rousseau-; “If I stop walking I don´t think anymore, my head walks to the pase of my feet”. The novelist is a vagabond that with his shothand in his hands, walks along the fields thinking. Hunting- regulated by a code that is equally aesthetic and ethical- is a reward in his search for nature: “I had never been in the meanders of Villavieja,-he says in a revealing way-, but it really is a spectacle. The river gets wider there and the water flows so peacefully that it seems lake. On the shore some elm trees grow and huge alder trees and the tamarind trees are so thik that the light barely passes through. Doves fly down to drink at the little sand islands that grow in the middle of the river…a fisher bird passes by like a lightening, I shot it twice but I wasn´t even close to touch it. The damn bird had a little bird in its beak, then I felt the wingbeat of a wood pidgeon and the bird just land at the tip of an alder tree that was just opposite my hunting post. I patiently waited and when the wood pidgeon decided to come down to drink at the little island I shot it down, it didn´t even emited a sound”. Here is how a hunter sees nature as a spectacle, feels the landscape with sensibility and remembers Virgil or Garcilaso or Fray Luis de León, and how a hunter does not suffer when he misses a shot and comes back with no kill. More than a conventional hunter he seems a priest of a novel that offices in the temple of nature.

Discurso inaugural, en Miguel Delibes

El escritor, la obra y el lector

Cristóbal Cuevas

Barcelona, Anthropos, 1992, p. 9.

It is no secret that the type of hunting that Delibes loves the most is the red partridge hunting, the real “queen” catch and number one objective of our Sunday excursions. […] The rest of catches that we have a look at the fields are mere complements. […] The same accidental motivation (as rabbits and hares) have in our catches a noble piece such as chocha […]

To this and the quails in summer id¡s what Delibes limits his hunting practice whose hunting preferences […] coincide with those of the modest hunters of Catilla. Once or twice I heard to some members of the hunting club Alcyón, to which Miguel Delibes was part since 1965, “¡How great are his tales about hunting but such a few ways of hunting he knows about!”. The truth is that indeed he knew about more hunting modalitites, but he only felt really captivated by the primitive forms of hunting, in which the hunter mst do everything, search the catch, wake it up, shoot it and retrieve it. A type of hunting in which shooting the shotgun and retrieving some bird requires to get exhausted and be precise with an stratergie in which a whole group takes part. A type of hunting, on the other hand, that does not end with the shot since retrieving the kill, examining it and hang it on your hanger was part of the hunter´s pleasures to which he will not give up or leave to the hands of an assistant. And a type of hunting that considers the final but no leat important part the victory of seeing the kill transformed into delicious culinary dish.

Cuatro décadas de caza con mi padre

Prólogo a Miguel Delibes: Obras Completas, V. El cazador

Germán Delibes de Castro

Barcelona, Destino-Círculo de Lectores, 2009, pp. XIII-XV.

I love nature because I am a hunter. I am a hunter because I love nature. It is both things. Moreover, I am not only a hunter, I am a protectionist; I am always in favor of proctecting all the species. People say that is a contradiction, but I say if I protect the species, I will have partridges to hunt in Fall. If I don´t protect them they will be gone, and that is exactly what is happening now. In that sense ther is no contradiction at all. On the other hand I am not a blind hunter only paying attention to the kill or the locations of the catch, I like enjoying the fields, watch the sunrise and the sunset, observe the scarlet colors on the bushes… If I also catch a couple of partridges and I eat the the following Tuesday, even merrier. But I never measure the fun by the number of kills.

fragmentos de entrevistas en República de las Letras

Miguel Delibes

núm. 117, junio 2010, p.10.

Miguel Delibes and his son Germán with their dog Grin. Quintanilla de Abajo (Valladolid), 1979.

At the age of seventy two and with half a hundred catches on the fields, the writer starts looking back. He is aware of this Lot´s complex and the consequences that it means and that he wants to deal with a sense of humor in El ultimo coto. “The episode of the story about lot makes sense for me if I think about the similarities with lumbago. I also became a salt statue last Thursday when I finished having a bath and I tried to rescue a sock that was lying on the floor”.

This tendency to melancholic revision of events could be dramatic for his depressive and pessimist ways if it wasn´t compensated by his long urban walks and, for him exhausting, hunting seasons. Even if some years ago his legs became alittle more of a “middle class” kind of legs, he continued chasing red partridges along the fields of Castilla. The title of his most recent book-El ultimo coto– makes inevitable reffernece to a farewell. I t won´t be me who really belives that. I think the Hunter will dies with his boots on. In fact, between the date of the Foreword- in which he announces his hunting retirement- and the date of his latest short story with the totle “La despedida” something like five years have gone by: from 1986 to 1991. And he keeps on going out on the search of whatever he finds, wood pidgeons or fine meat quails…For Delibes his physical decline coincides with the extinction of the wild partridge, a sign of worse and more severe declines.

The fact is that if Delibes decided to end seventy years of hunting adventures it wouls also mean the end of that series of precise writing, beautiful, and classical books which lastest title is El ultimo coto, a highlight piece of work that started in the form of a novel with Diario de un cazador and in for of a chronicle with La caza de la perdiz roja. (About a thousand pages which would be enough to conside Delibes an exceptional writer.)

Winter text in which are decribed sleepy landscapes and wet foggy early hours, text with happy feelings so breve as the rays of sun light that find their way throughout the castillian wastelands or the happiness of a good catch. “I caught for the comunity satchel five red partridges, one hare and a rabbit… Moral of the story: I still can catch them. Which doesn´t mean that I kill all the partridges I shoot. Yesterday I spooked the ones that came on my way, only that, and those which flew like lightening passing me by I couldn´t even smell them. Becoming old has its prove in those kind of things”.

Introducción a Conversaciones con Miguel Delibes

César Alonso de los Ríos

Barcelona, Destino, 1993, pp. 11-13.

Delibes was a hunter […] but he was a selective hunter, very attentive to the preservation of the species- animals and plants-; preocuppied by the tranformations of the agriculture and its consequnces on Nature; intolerant with the industrialization of hunting; opposed to the illegal hunting and all the excess in hunting, in all these aspects a tireless professor for the rest of Spanish hunters. His lessons are evident in books such as La caza de la perdiz roja, El ultimo coto, Con la escopeta al hombre, Mi vida al ire libre, La caza en España and many others.

Probably nobody made a greater effort to reach closer such opposite worlds: hunting and Nature preservation, just because of this effort he is worth of our respect and aknoledgement.

El credo de Miguel Delibes, en Aves y naturaleza

Eduardo de Juana

Revista de la Sociedad Española de Ornitología, núm. 3, Verano 2010, p. 32.

For me the acceptance of the hunting titles of Delibes has always caught my attention.[…] In my case[…] hunting is an activity that is not appealing at all, I could even dare to say that the only feeling that I have towards a “so called” sport is rejection. Nevertheless I have read all those works form Delibes with attention and fondness. I was never completely convinced by the preservation concepts that Delibes claimed in favor of hunting, but in his books where he chases red partridges, rabbits and hares are in the group of book that I sometimes re-read. Leaving aside the hunting topic there must be thus other aspects that make these books attractive.

In the first palce I think, we fell attracted to the sincere and self confessional tone of a man that has lived in an alert way the unexpected events of our time. He offers cold, aseptic and hyperbolic stories […] of the hunting practice and are often interwoven with the self experiences, emotions and fellings of the narrator provoked by the landscape or an anecdote. Without any tenderness the human being that the hunter hides can be seen in these stories. That is why he was ver y rght when he defined himself as a hunter that writes. It seems that he is not creating literature, but literature is there in all his stories with his simple way of saying things […]

The reason why these stories catch us, independently of the topics, comes from the fact that this man from Valladolid offers a clean, clear, rich, expressive and simple language with which he says many things […], a common language […] that the writer rescues […] because he is keen on the precise and exact language and giving things their correspondant name.

[…] That affection and simplicity so typical of Delibes, a pure and alive language that he uses to construct pilots of his books and testimonial chronicles. All those aspects only serve to a precise conception of Literature as a form of communication and a way of directly transmiting a personal experience. And there, I think, it is the success of his lietarture, saying things in a close and loving way that readers accept as an authentic way of expressing real life experiences.

Un decir próximo y entrañable, en Las constantes de Delibes

Santos Sanz Villanueva

Premio Cervantes 1993. Diputación de Valladolid-Fundación Municipal de Cultura, 1995, pp. 42-43.

DELIBES

Cinema and theater

Apart from his relationship with the cinema due to the constact adaptation of his novels, Delibes has another facet not so well known and that I would like to point out here: I´m referring to his work as a cinema critic in the newspaper El Norte de Castilla, indeed in his first phase an editor of that newspaper. Delibes himself always said that those critiques were never too professional, they just cover punctual need of the newpaper at an urge moment; but I am sure that if we revise them carefully, we could doubtless find interesting elements that very likely will match with the notable cinema interest that Delibes always showed. I can personally give prove of this since I know about his constanct participation in the Semana del Cine de Valladolid (SEMINCI), and his presence in the periodical cinema cycles that were yearly organize as well as his frequent assistance to the proyection of movies in the local theaters in Valladolid. I would even dare to say that his fondness in cinema provoke an influence in a double way: the precise character of his novels to be adpted to the language of the cinema and the influence, that I consider, the language of the cinema had on some of the narrative works of Delibes.

La imagen y la palabra, Mesa redonda, en Miguel Delibes

Premio Nacional de las Letras Españolas 1991

Fernando Lara

Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura, 1994, p. 245.

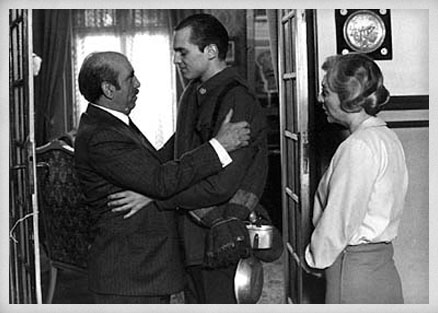

Miguel Delibes with Juan Diego. Filming of “Los santos inocentes”, 1984.

When I read “Los santos inocentes” I was shocked by the strenght and the virtue of Miguel Delibes, on the other hand I find those characteristics frequent in other Spanish writers from the fifties: their extraordinary listening skills… They are writers who listened in a wonderful way to the people in bars, on the streets, on the fields, and when they make the characters of their novels speak, we can immediately recognize them, they are plausible and authentic characters…

Entrevista con Diego Galán.

Mario Camus

El País Dominical 13. 05. 1984.

Working with any of the texts from Delibes offers a great advantage, and everyone who has done so owe him, since you can learn an essential lesson: the essential concept itself. Delibes always writes straight to the point, he has the skills to find in his writing the key to reach the sensibility, and goes straight to the heart and the intelligence of the reader. His capacity to hint at concepts is amazin. He offers a vision of life and the world that can seem objective and realistic, but the truth is that the vision is a very personal interpretation in which plays a key role the election and description of characters and situations, highlighting some of them and hiding other in such a way that the created situation and the generated emotion by this situation reaches out fully and straight. Even when it comes to select- cinema and television must select and summarize the literary work- the language in Delibes is so fertile that offers yu a wide varity of possibilities each of them more versatile and convincing.

La imagen y la palabra, Mesa redonda, en Miguel Delibes

Premio Nacional de las Letras Españolas 1991.

Josefina Molina

Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura, 1994, p. 247.

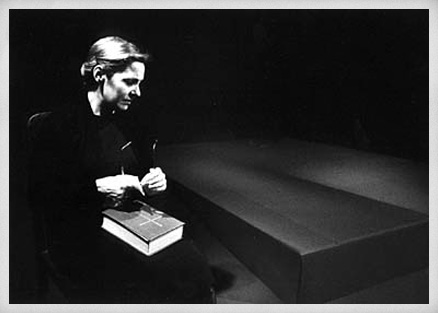

The actress Lola Herrera representing “Cinco horas con Mario” (“Five hours with Mario”), 1979.

“De la novela al teatro” is the title of this afternoon´s round table. Of the novel from Miguel Delibes to the theater that is ased on those novels. As you all know, Miguel Delibes, apart from being a great novelist, has lived the experiences that some of his novels have been adapted to the theater play having great success and public acceptance and critique and also had the virtue that the adaptation from novel to play they managed not to lose their communication with the audience, neither their fresh language nor the strength and emotional humanism of their extraordinary characters.

De la novela al teatro, Mesa redonda, en Miguel Delibes

Premio Nacional de las Letras Españolas 1991

Andrés Amorós

Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura, 1994, p. 259.

Recently I returned from the beautiful village of Alburquerque, in Extremadura, where Mario Camus has been filming a movie base don my novel “Los santos inocentes”. This little excursion has been very productive for me, since on the one hand I have been able to check myself the temperance and mastery of Camus as a cinema director, and on the other hand I could also appreciate the ductility of Paco Rabal and Alfredo Landa in two roles extremely difficult to play. This is not, on the contrary of what some people have claimed my first encounter with the cinema. With the cinema in its literay-technical side I contacted twenty years ago with the occasion of the dubbing into Spanish of the American movie “Doctor Zhivago”, that just a few days ago we could watch on TV again. Miy mission was very specific: revising in a litery and careful way the raw dialogues that I was handed in. So this mission had two main targets, first adapting those dialogues in a way that once they were dubbed into Spanish wouldn´t lose their effectiveness neither their euphony. The second of these missions was to adapt those revised dialogues as close as possible to the lip moves of the actors and actresses. A precise dubbing requires of these demands: that the sounds that a person produces on screen don´t result too short but neither they exceed the lip moves that the protagonists make. This task is not too difficult when it comes to adapt long dialogues but it becomes annoyingly complicated when we look at shor dialogues, where the reviser must limit to the number of syllables that the actors pronounce. In a professional dubbing it is not acceptable that an actor moves the lips without receiving any sound from them, but neither that we receive the sound without the actor moving the lips. So is, that if the raw translations results in a sentence of twenty syllables, whereas the English phonetics says the same sentence but producing only ten syllables, the person in charge of the dubbing, throughout the necessary sources, has to reduce to ten syllables a sentence that originally required twenty.To this respect I remember in this movie a scene when a prissioners train was led to Siberia, one of the prissioners faces one of the guardians and tells him off with a sequence of short insults, three to be more specific. My duty in this case was to reduce to seven syllables those insults, and facing the difficulty to find in the Spanish language three words short and expressive enough, I opted to choose only two words but very resounding and conclusive: “lacayo y lameculos” (lackey and asslicker) the later a bit too harsh for that time which on the day of the premiere of the movie in Valladolid, made the woman sitting next to me in the theater to turn to her scort and said to him: “How funny you see, they also use the word lameculos in Russia!”.

This experience with dubbing was very useful for me since I have always been in favor of the braveness of the language, saying as much as you can with the smallest number of words. After this, another three colaborations of minor responsibility came along, such as the literary revision of movie scripts or perhaps a bit of advice in the shooting of some movies thathad any of my novels as theme. In this sense my first experience was “El camino” (“The Path”), movie which was directed by Ana Mariscal in the little village of Candeleda. I remember that I was surprised by the slowness of the creational process and also by the fact that the content was not filmed in a lineal way, from the beginning until the end, but on the contrary was filmed in segments and fractions without any logical sequencing. I also remember that the children would get tired because the filming took so long and it was very exigent, and when Ana Mariscal began the secene in which Daniel, el Mochuelo, leaves a thrush on the hands of his dead friend Germán, el tiñoso, the kid who played the role of Germán had fallen asleep inside the coffin, such a scene caused great distress in his mother who was observing the scene, but such anecdote made the scene much more credible.

“Retrato de familia” directed by Giménez-Rico was the cinema adaptation of “Mi idolatrado hijo Sisí”, and with this movie the lesson was different. The novel has three hundred fifty pages, which is the equivalent of six or even eight time the length of a normal movie scrip, which in this case made the cutback rather extreme. Giménez-Rico solves the problem in a very wise way by reducing the plot to the third of the three books that conform the novel instead compressing the dialogues. He only certain flashbacks to the first books when it was absolutely necessary for him to introduce and describe any of the characters. I learnt another thing in Retrato de familia and that is that even if it is desirable to avoid an excess in erotic content, in this case images can be allowed to use a bit of this since they are mute and the camera leaks through the words as the rays of sun go thorugh a glass. Giménez-Rico taking advantage of the new period of liberalization, made the characters live the rawest scenes without changing a single coma in the script. Images spoke on their own when the words were paused.